Postpartum depression is an illness that affects women shortly after giving birth. It can happen to anyone of any age, profession, social background, or wealth. Therefore, it’s essential to be aware of the symptoms and know what you can do about them. Most women experience

Postpartum depression, or PPD, is a mental condition impacting roughly one in five new mothers. It is a comparatively common mood disorder that can occur within the first year after childbirth. Postpartum depression symptoms include low self-esteem, anxiety, irritability, and depression. Most episodes of PPD are relatively mild and will pass on their own. How long can postpartum depression last? Ordinarily, it goes away after a few months. However, some cases can be severe and even life-threatening.

What Causes Postpartum Depression?

The etiology of postpartum depression is not entirely known, although it’s thought that hormonal changes are partly responsible for feelings of exhaustion, low moods, and difficulty sleeping. Additionally, some studies suggest that a combination of

Women who suffer from this condition report symptoms that includes:

- Sadness

- Sleep deprivation

- Increased anxiety

There is a

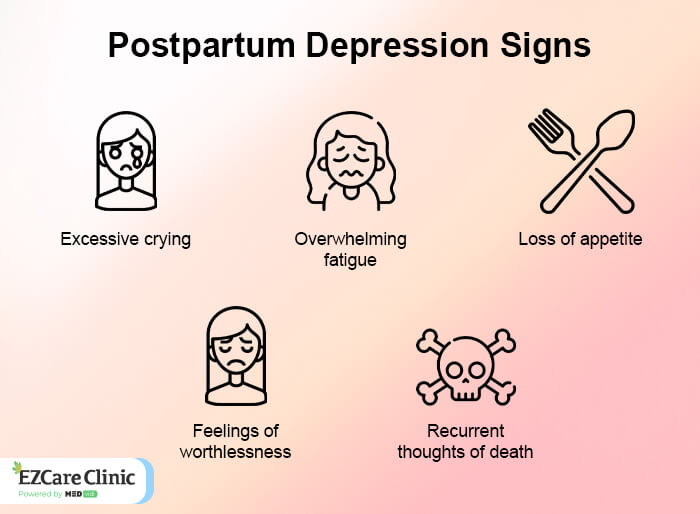

What Are the Symptoms of PPD?

Postpartum depression symptoms develop after childbirth. According to the

- Mood swings: A change in mood or behavior for no apparent reason.

- Weight loss: Changes in appetite or weight gain/loss, when not wanting to eat, or being unable to lose the extra weight after delivery.

- Low Energy: Lack of energy, fatigue, and poor concentration; diminished interest in pleasurable activities; sadness, low mood, and hopelessness that can last for months after giving birth.

- Sleep deprivation: Difficulty concentrating in the morning, trouble getting off to sleep at night, waking up too early, or staying awake all night while being unable to sleep more than two hours at a time.

- Irritability: Angry outbursts or feeling constantly annoyed with your partner, family, and friends.

- Thoughts of suicide: Feelings of hopelessnes and wanting to run away from the depressing thoughts by ending once life.

- Psychological guilt: Feeling responsible for things that are not your fault.

- Loss of interest in work or other activities: Feelings that these things are not necessary to you anymore.

- Connection with your baby is absent: You may feel helpless and confused about what to do next.

So, how long can postpartum depression last?

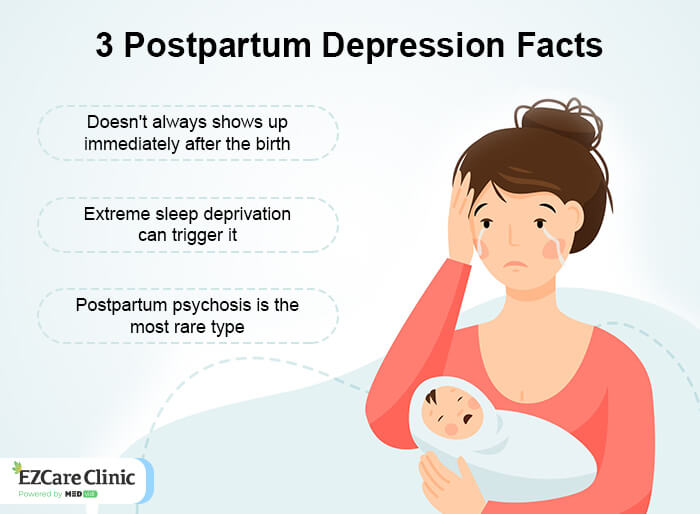

Postpartum depression typically strikes within a few weeks after the mother sees her newborn for the first time. This is, of course, influenced by her unique situation and history. Some cases of PPD are more severe than others and can last a few months to years if left untreated, but it’s a relatively uncommon condition.

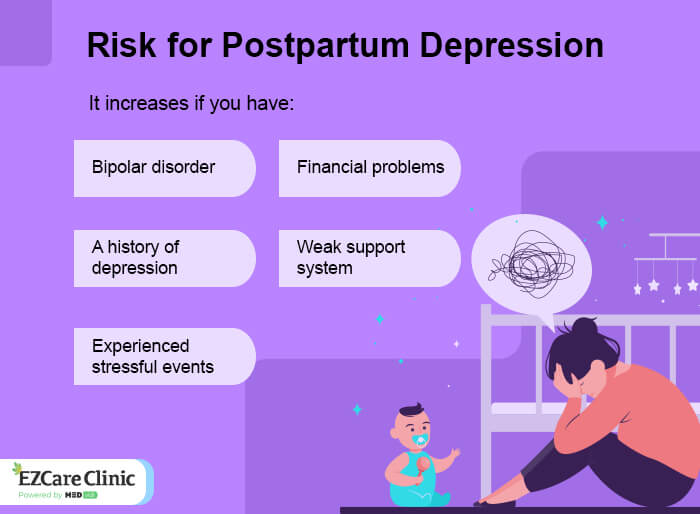

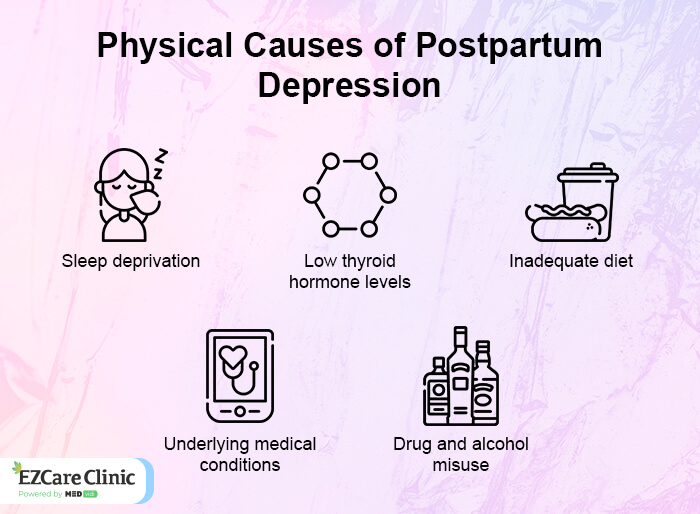

Postpartum Depression Causes and Risk Factors

Many factors can contribute to the development of postpartum depression. Some of these include:

- Hormonal changes : Studies have shown that a decrease in progesterone levels can trigger the onset of PPD symptoms, as well as a drop in estrogen levels after childbirth.

- Unwanted pregnancy: A trauma or sadness over giving birth is one main factor within this category.

- Childbirth history: Women who have experienced severe anxiety and stress before or during childbirth are most likely to develop PPD as well.

- Early parenthood: New mothers who have not had time to build up experience and confidence are more likely to feel overwhelmed by their responsibilities immediately after giving birth.

- Feelings of isolation: Those who do not have a supportive family, or those who have suffered a tragic loss or event, may be at risk of developing PPD.

- Previous mental illness: Women with pre-existing mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder,

borderline personality disorder[5] , and anorexia are also at risk of developing postpartum depression. - Unexpected news: The baby suffers from an illness or disability or has passed away soon after birth.

- Pregnancy complications: If the pregnancy has been complicated in some way, e.g., by pre-eclampsia or other complications during childbirth.

- Lack of proper support: Social isolation and a lack of social support coupled with a previous case of severe depression.

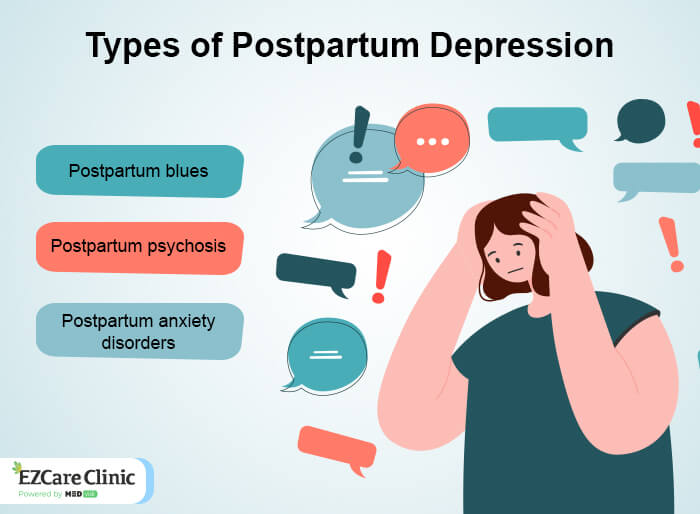

Types of Postpartum Depression

When a woman feels that her life is not worth living, when she can’t hold down a job or maintain relationships with family and friends, it’s time to seek help. Postpartum depression can be treated thanks to a health care provider or a trained counselor. There are several subtypes of PPD, including:

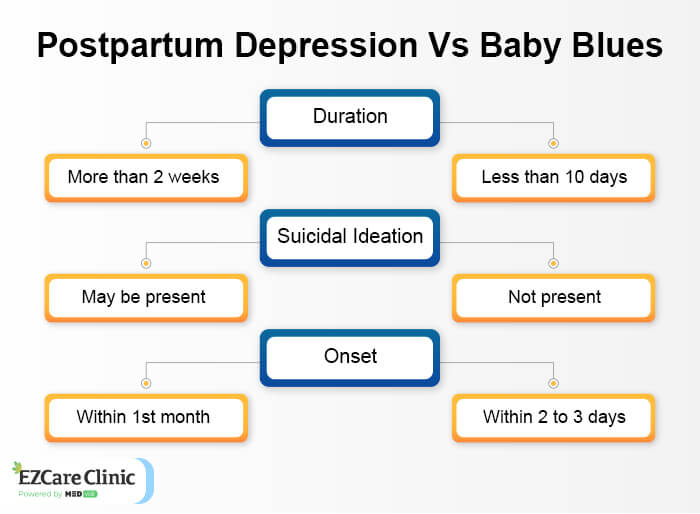

Baby Blues

It is not typically considered serious and does not require medical attention. It is thought to be related to hormonal changes and is usually mild. The

Postpartum Psychosis

It is a rare but severe condition where the symptoms of depression are severe and interfere with day-to-day activities. The mother may become detached from reality and cannot tell what is real and what isn’t. She may suffer from delusions or hallucinations, including believing that an imposter has replaced the child. In some cases, she may have suicidal thoughts.

Postpartum Depression With Psychosis

This type of PPD is similar to postpartum psychosis in that the symptoms are severe and interfere with day-to-day activities. However, while in postpartum psychosis, the mother may have delusions or hallucinations and express paranoid thoughts. With this particular condition, depression is present, but it is not major depression.

Postpartum Anxiety

Postpartum anxiety refers to those who experience anxiety surrounding giving birth and the first few weeks after giving birth. These women often have the feeling that something terrible is going to happen during this period. Sometimes these women suffer from severe anxiety and fear for their physical well-being and their baby’s physical health.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

When mothers experience severe trauma before or after childbirth, they can develop this condition. The symptoms include intrusive thoughts and memories of the event and hyper-arousal that can last for months or years after the event occurs. Some mothers also experience a sense of detachment from reality and sleep problems. Women who have had postpartum depression may have a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms in the future or may suffer from postpartum depression again after subsequent pregnancies. You can reduce the risk factors by taking care of your health before, during, and after pregnancy, developing a support system, and finding someone to confide in before the related conditions occur.

Postpartum OCD (Obsessive-compulsive Disorder)

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) mainly affects women by striking during the childbearing years and causing extreme anxiety about having an unhealthy baby. Obsessions can include:

- The obsessing mother will think that something terrible will happen to her infant, or that her baby has a serious illness that no one will notice but her.

- The obsessive mother will feel overwhelming urges to do or say something inappropriate in response to her fear, such as testing her baby’s reflexes frequently or sterilizing everything she comes into contact with.

- The obsessing mother may engage in “compulsive ritualistic behaviors” described by others as counting, checking, or cleaning compulsively. The rituals become an obsession, and the woman will feel relief when completed. These obsessive intrusive thoughts are triggered by the birth of a child and the responsibilities of parenthood.

Epidemiology of Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression is not a rare occurrence. It is estimated that about one in every nine women will suffer from postpartum depression sometime during the first year after giving birth. It has also been estimated that about 10% of women will struggle with postpartum anxiety or OCD.

Why Does Postpartum Depression Happen?

According to Mayo Clinic, the most common form of postpartum depression is dysthymia. Dysthymia is defined as a chronic, low-grade mood disturbance that may last for years. Dysthymia is often seen in young women who have experienced sexual abuse as a child, or women who are victims of incest or rape. Symptoms include loss of interest in activities that used to be pleasurable; feelings of emptiness; irritability and anger; poor self-esteem; decreased energy and fatigue; changes in appetite and weight; and insomnia. Sufferers may withdraw from their usual obligations at home or work; some may move back in with their parents for a time to hide the postpartum depression symptoms and receive help from others with daily tasks.

Other Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression?

As mentioned previously, a

- irritability,

- excessive crying,

- sleep disturbance, and

- breast tenderness.

The most common behavioral symptoms begin after two weeks postpartum. They include decreased interest in baby care, withdrawal from family and friends, isolation from the baby, changes in appetite or weight loss, and angry outbursts. There is currently no cure for PPD. Postpartum depression treatment aims to prevent depressive symptoms (prevention), helping the family adjust (therapy). Numerous studies support effective treatments for PPD, such as medication and psychotherapy. A psychiatrist may prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) such as fluoxetine or sertraline. Antidepressants include SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), bupropion, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Other antidepressants that may also be prescribed include mood stabilizers, such as lithium. Other medications may be prescribed to improve sleep, which would increase the likelihood of the mother bonding with her baby. The psychiatrist may take note of complications that occurred during the pregnancy or delivery that could have affected the onset of PPD. The psychiatrist will also gather information on how well the mother is functioning in many areas such as work and family issues. Postpartum depression treatment is usually a combination of psychotherapy and medication. Several weeks of psychotherapy help the mother develop a more positive attitude about herself and her child and how she relates to her child. In some cases, psychotherapy can be effective without medication. Medication may be needed for several weeks or months to lessen the severity of depression symptoms.

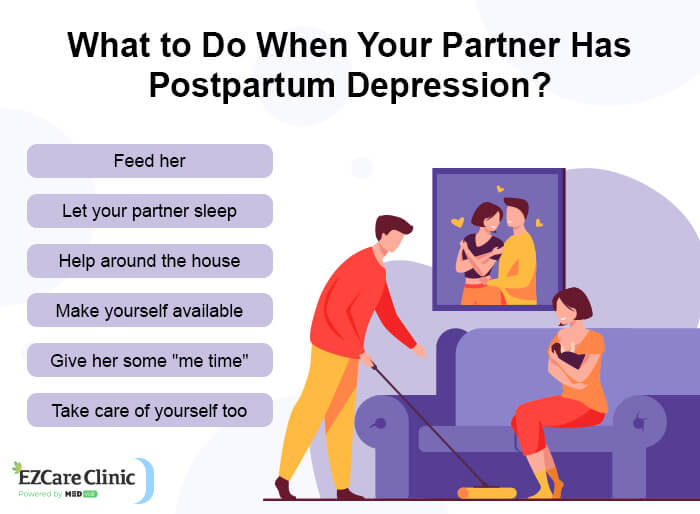

Family and Postpartum Depression Treatment

Families are also encouraged to create a support system to cheer up the mother, help with baby caregiving, and encourage her to take antidepressants. Social support such as friends and family members can significantly decrease depressive symptoms. Friends and family members can also be helpful by offering a listening ear when the mother is feeling down. The goal of postpartum depression treatment is to help the mother develop a good relationship with the baby, feel good about herself and other aspects of her life. The mother should also be in the best physical and mental health possible. There are many self-help treatments for PPD that will help mothers get through this time:

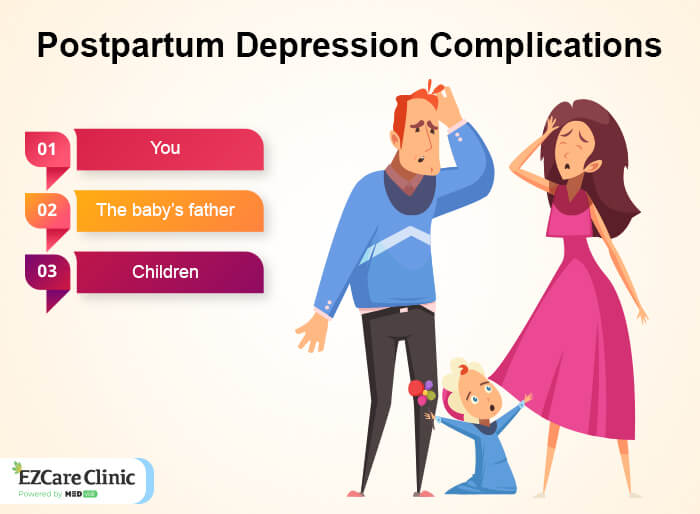

PPD has been described as being harder to treat because mothers tend to be more worried about their child’s well-being. This can lead to greater guilt and more severe symptoms of PPD. Women with PPD must seek treatment because they are more likely to neglect themselves and their children if they do not receive an intervention. PPD can be effectively treated in a way that allows women to return to work, keep the family together, and develop a healthy bond between themselves and their children. The mother must feel like she is cared for by her partner and others to care for her baby. This self-worth leads to her being able to take care of herself and her partner. For postpartum depression treatment to be successful, it must address the needs of each family member, from mother to father. Family dynamics and function are actively involved in this process. PPD can have major effects on a mother, child, and family. The mother may feel guilty about her depression and the care she cannot provide for her child. She may have difficulty bonding with her baby, which results in the baby developing attachment issues or playing problems. She may decrease her physical activity due to depression and be unable to keep up with the demands of parenting. Depression can negatively affect many parts of her life, such as work, school, social life, etc. because she is not functioning at a high level emotionally. These effects can lead to difficulties in completing daily tasks, leading to increased stress levels. Mothers with PPD may spend more time away from the child and become less involved in childbearing. These changes affect the child’s development and the father-child attachment, which can lead to a variety of developmental, emotional, and cognitive problems. The father may be affected by PPD if he feels like he cannot help with caregiving or comfort his partner.

The risk of postpartum depression is highest among teenage women, young mothers, and those with less education. The risk of PPD also increases when the mother does not have effective emotional support, for example, being isolated from family and friends. The specific hormone changes which occur in the postpartum period also play a role, especially in cases where both parents experience PPD (e.g., fathers whose wives are pregnant). Some research has found that mothers who experienced depression during pregnancy were more likely to suffer from depression after giving birth, just as some women experience menopause-related mood disorders. Several organizations provide support and education for women who have experienced PPD. These organizations also help identify local resources for postpartum mothers, fathers, and families. Some postpartum organizations offer group meetings for men to learn about the effects of postpartum depression on their partners and sex lives. A support group, Mothers, and Fathers of Babies with Special Needs is available for fathers and their partners experiencing depression after the birth of a child with special needs. Recent research has begun exploring the therapeutic effects of music therapy in treating PPD. A study found that women who participated in a music therapy treatment program were more satisfied with their lives post-treatment than those not part of the group. In a study at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, women with postpartum depression were found to benefit their mental and physical health when they participated in music therapy. Therefore, postpartum depression self care routine can involve a new mother engaging in dancing sessions.

Substance Abuse and Postpartum Depression

Substance abuse may also occur during PPD. Research byNegative Effects of Maternal Depression

During pregnancy, maternal mental health conditions may result in adverse effects on the child and the mother. The following health problems have been associated with maternal depression:- Cardiovascular disease

- Constipation

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Breathing problems

- Increased risk of other disorders

- Pregnancy complications (e.g., miscarriage, low birth weight, stillbirth, premature infant delivery, anxiety, or depression related to these events).

Consequences of Maternal Depression on Child Development

Maternal depression directly correlates with child development and can negatively affect it. The effects vary depending on the age, and they can be as follows:Prenatal

During the prenatal period, maternal depression can lead to lower fetal birth weight and more preterm deliveries, small for gestational age infants, increased neonatal mortality rate, and neurobehavioral problems.Infant

The infant can experience permanent effects (early and later childhood), including neurobiological, behavioral, emotional, and cognitive changes. These effects can be seen in the areas of attention, language, psychomotor and social intelligence.

Toddler

Toddlers are the most affected by maternal depression. They can present cognitive, motor, and language development delays, neurobehavioral problems related to anxiety/depression, aggressive behavior, and a lower sense of personal efficacy.

Preschool

The impact on these children is more than any other age because maternal depression leads to parenting practices that have a negative effect on the child. The child can develop symptoms of anxiety and depression and show changes in personality characteristics (become introverted or aggressive).

School-age

Depression has the same consequences as preschool age but with an increase in undesirable behaviors like aggression and delinquency.

Adolescent

Another period of significant vulnerability for the child is that maternal depression leads to significant developmental delays and increases the likelihood of depressive symptoms later in life.

Diagnosis of Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most common complications of childbirth. Diagnosis of postpartum depression is currently clinical, with maternally self-reported depressive symptoms, observed behavior, and maternal history of depression. The diagnostic process usually begins with a visit to the doctor or midwife. Thereafter, it is recommended that the woman fill out a questionnaire that will give various information about her physical and mental state, although it is also possible to get an accurate diagnosis using observation and questioning alone. The American Psychological Association has formulated the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for PPD postpartum depression screening and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for more specific diagnoses. Both tools are short self-report instruments that can be applied by the patient herself or by health care professionals.

Screening for Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression screening is important because of the potentially detrimental consequences of PPD (infant distress and impaired mother-child interactions) and because untreated depression can lead to a chronic condition. Patients should be asked about depressive symptoms during the perinatal period, preferably during prenatal care, since symptoms may emerge during pregnancy or after delivery. The American Psychiatric Association recommends that health professionals ask pregnant women about depressive symptoms from the first prenatal visit through 3 months postpartum, followed by a more in-depth assessment at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum. Psychological tests can be applied at the first hospital visit.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen (EPDS)

The main questionnaire used to obtain information about maternal depression is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), which has ten questions with three response options. The objective is to assess mood changes, sleep, appetite, feelings, and thoughts of the mother compared with before pregnancy. The results are analyzed by a qualified health professional and presented in a score ranging between 0-30 points. A score above 13 points indicates depression that requires postpartum depression treatment. The EPDS questionnaire, originally validated for depression during pregnancy, has been adapted and validated for assessment of the postnatal period. During pregnancy, the questions are asked about symptoms since the last interview and in the postpartum period since delivery. It is crucial to remember that different populations may present with different cut-off values. EPDS results can be compared across various scales, including the NPI and the Zung Depression Scale.

2-Question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2)

The PHQ-2 is a self-report questionnaire with two questions that incorporates DSM-IV protocol. It is also a screening tool that can help health care providers to detect depression among pregnant women. The first question asks if the mother has felt sad or down in the last week, and if so, how often it happened. A response of “often” may indicate depression, whereas an answer of “none of the time” does not. The second question asks if she has lost interest in activities that she liked during the previous week. Note that if the PHQ-9 reading is greater than 10 this means that there is 88% sensitivity and 88% specificity for major depressive disorder. Patients should be asked about depressive symptoms during the perinatal period, preferably during prenatal care, since symptoms may emerge during pregnancy or after delivery.

9-Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The 9-PHQ-9 is a short self-report questionnaire that asks the patient to indicate how often they have experienced nine criteria that frequently accompany PPD, such as:

- Depressive symptoms in the last two weeks (SCID).

- Pessimistic thoughts in the previous week.

- Difficulty concentrating or remembering things.

- Sleep disorder (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep).

- Recurrent thoughts of death/suicide.

- Change in appetite/feeling too full or hungry.

- Reduced energy (having a lack of energy).

- Impaired concentration or thinking

- Feeling sad or hopeless.

A score of 2 or more points on the PHQ-9 during the postnatal period, instead of a score of 1 or less on the PHQ-2 at any time during the postnatal period, is indicative of depression. The 9-PHQ-9 has 97% and 91% sensitivity and specificity, respectively, for detecting PPD in general populations. Postpartum blues may be overlooked due to the difficulties in diagnosis; however, it can be a devastating experience for both mother and baby that lead to a poor psychological adjustment in both mother and baby. Depression is associated with physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral impairments that may interfere with functioning normally. It is associated with decreased maternal self-esteem (ego strength, emotional expressiveness) and increased anxiety.

Pharmacological Treatments for Postpartum Depression

There are many treatment options for postpartum depression. The more effective treatments are psychotherapy (individual talk therapy or group therapy), pharmacotherapy (antidepressants), or both. Self-help programs are also an option at home but not a substitute for treatment.

Antidepressant Medication

Medications are the first-line treatments for postpartum depression. Antidepressants may be prescribed for women who do not want or are not eligible for psychological interventions. They are used for mothers with moderate to severe depression or those who cannot wait for a psychotherapist. Antidepressants are also used to treat postpartum psychosis, a rare but serious condition characterized by hallucinations and delusions.

Postpartum depression and breastfeeding also clash during PPD treatment. There have been concerns about the safety of antidepressants during breastfeeding, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, research shows no risks to the infant if breastfed infants receive antidepressant medications. The safety of antidepressants during breastfeeding is determined by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The AAP guidelines indicate that treatment with SSRIs during breastfeeding is generally safe. The AAP recommends treating postpartum depression with an SSRI in consultation with a health care provider to ensure the safety and efficiency of the medication, and then planning for weaning off the drug. If breastfeeding is not necessary, it is recommended that mothers stop breastfeeding when treatment starts. If breastfeeding is essential, it is best to wait until the baby is one month old to begin treatment. Mothers can start on a lower dose or split the daily dose into two smaller doses given at intervals during each day. After the baby is one month old, mothers can decrease the quantity to half a dose once daily. If withdrawal symptoms occur after stopping the treatment for postpartum depression medications, the mother can resume taking the medication until she is ready to stop treatment. Medications should be weaned off slowly and under careful supervision due to risks of relapse or discontinuation syndrome associated with abrupt discontinuation of antidepressants. Breastfeeding should be decreased as the treatment for postpartum depression medication begins and stops when treatment is complete. Generally, mothers will not have enough milk to sustain infants during weaning from antidepressant medication. Mothers who are not breastfeeding may use formula while taking the medication, but they may need to pump and dump their milk before or after taking it.

Medication Effects on Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression

In general, SSRI antidepressants have minimal effects on lactation. The most commonly prescribed SSRIs are fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft). Fluoxetine is generally considered to be as safe as other SSRIs in breastfeeding mothers. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors do not appear to affect prolactin secretion because of their actions at serotonin receptors in the hypothalamus. Nefazodone is also considered relatively safe, but less research supports its safety than other antidepressants. Even with the limited research associated with antidepressants in breastfeeding mothers, it appears that most mothers can continue breastfeeding while they are on antidepressants. Breast milk thins and the infant nurses less often. However, this is usually due to reduced milk supply, not to decrease milk volume itself, as most mothers’ milk will increase as they wean off the drug. The risks of breastfeeding while taking antidepressant medication are similar to other medicines that are used infrequently in mothers with no infant at risk of rejection (e.g., penicillin).

The most common side effects that may occur during lactation include irritability, sleep difficulty, and diarrhea. These side effects usually go away within a few days or weeks after stopping or changing the drug dose. In rare cases, irritability or insomnia have required mothers to reduce their treatment for postpartum depression medications or stop breastfeeding. If a mother has problems breastfeeding, stopping antidepressants and treating the pain caused by depression may solve the problem. If a mother stops taking an antidepressant and her milk supply goes down, she can take more milk supplements while her milk supply recovers. If she cannot produce enough milk, she should consider bottle-feeding formula instead of breastfeeding.

Hormone Therapy

There is a direct causal link between women suffering from postpartum depression and hormonal imbalance. It is believed that this is due to the changes in their hormones that occur around six weeks postpartum. Unfortunately, not many people understand that hormonal imbalance is real and plays an essential role in postpartum depression. Changes in levels of estrogen and progesterone during pregnancy can play a significant role in the formation or aggravation of symptoms of postpartum depression. The changes occur both in the mother’s body and her brain. This is attributed to the high estrogen levels during pregnancy and their action on the brain’s neurotransmitters, directly influencing mood and behavior. While postpartum depression is not directly related to stress, anxiety can aggravate the symptoms. The presence of a new baby and an already stressful situation may mean that a new mother is also under more intense emotions than usual, contributing to developing postpartum depression. As hormones play a role in having postpartum depression, therefore hormone therapy can be a suitable treatment for postpartum depression. This treatment can help to reduce the symptoms of postpartum depression by restoring the hormone balance and thus making the body’s response more normal. In fact, certain hormones like estrogen and progesterone help to combat depression. If you have high estrogen levels, it can help make you feel comfortable in your body again and be happy. Estrogen is responsible for many things, such as keeping your skin soft, protecting your bones from becoming brittle, keeping your muscles toned, and helping you maintain a healthy body weight. Progesterone is responsible for making the uterus receptive for the implantation of a fertilized egg. Progesterone is also essential in maintaining pregnancy. As postpartum depression is caused by a hormonal imbalance that results in low levels of estrogen and progesterone, hormones should be replenished to treat postpartum depression. The above suggests that estrogen and progesterone therapy may effectively prevent the risk of postpartum depression by increasing the expression of serotonin transporters rather than just by raising brain serotonin levels. At present, there is a popular treatment known as Hormone Therapy that helps balance estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone levels. Hormone therapy involves administering natural hormone extract or a combination of medications to help boost the production of hormones to normal levels. There are many advantages to hormone therapy, such as convenience, cost, and ease of use. A doctor can adjust the number of administrations and dosage according to a woman’s needs. Hormone therapy has been used in Europe and the U.S. for several years. It is considered to be very safe while still effective.

Psychological and Psychosocial Treatments for Postpartum Depression

Psychological and psychosocial treatments for postpartum depression are effective. Most women with postpartum depression prefer psychological interventions to drug therapy. There is tentative evidence that psychotherapy and breastfeeding are associated, in the short term, with a reduction of symptoms of postpartum depression. Psychosocial interventions can be provided by trained health workers, either as single interventions or with other forms of intervention. Correct information about the nature, course, and treatment of postpartum depression can help women to understand their condition and make informed decisions about treatment options. Women who choose not to breastfeed should be informed that this decision is unlikely to have any long-term adverse effects on the child’s development.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

IPT is time-limited psychotherapy for depression, commonly used to treat postpartum depression, that focuses on problems in interpersonal functioning and the individual’s intrapsychic processes. IPT has been studied among women with postpartum depression in randomized controlled trials. IPT reduced the risk of having a depressive episode 6 to 12 months after childbirth, and also reduced depressive symptoms in the short term.

Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is an example of psychological treatment for postpartum depression that has been studied extensively. CBT has been found effective in the prevention of recurrent depression. Using a very straightforward approach (e.g., 30 minutes per session), CBT for postpartum depression can be effective and safe. It is unclear what the best specific combination of therapies would be to prevent recurrence or improve treatment outcomes, but psychoeducation or individual counseling may be particularly effective. CBT is a psychosocial treatment that focuses on behavior and cognitive processes, such as faulty beliefs and maladaptive assumptions, which maintain depression. It is a time-limited therapy used to treat women with postpartum depression in most of the studies that have been published. The relevant randomized controlled trials results indicate that CBT reduces the risk of relapse for up to one year after childbirth and improves depressive symptoms in the short term.

Nondirective Counseling

Non Directive counseling is a simple, non-structured approach to support women with postpartum depression. It is based on acceptance and commitment therapy principles, which advocate taking an active rather than a passive approach. It views symptoms as an opportunity to learn more about one’s experiences and emotions. Nondirective counseling has been found effective in reducing the severity of depressive symptoms among women with postpartum depression in at least three studies that have been published. In general, nondirective counseling is safe and well-tolerated by most mothers.

Family Therapy

Family therapy has been proposed to help families with postpartum depression, but it has not been evaluated. It is unclear whether the treatment is effective and can be used to treat postpartum depression. Some studies suggest that family therapy may be helpful for mothers with postpartum depression and infants who are affected by maternal symptoms.

Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

MBCT consists of two main elements:

- Mindfulness training and;

- Relapse prevention component.

Mindfulness training aims at developing awareness of one’s thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and external perceptions. MBCT has been shown to be effective in preventing depressive relapse and reducing depressive symptoms. MBCT can be provided by trained health workers, either as single interventions or with other forms of intervention. There is a need for studies to explore the efficacy of MBCT for improving mothers’ well-being, parental-infant bonding, relationship with the partner, and quality of life at 1 to 2 months and at six months postpartum.

Peer and Partner Support

It is unclear how practical peer and partner support can reduce the risk of depressive symptoms or recurrence among women with postpartum depression. A few studies have found that it enhances recovery, but this may be related to the nature of the intervention rather than an independent effect. Some individuals are more likely to benefit from this type of support than others. At least one study suggests that it is associated with more improvement in the quality of life where it is provided.

Peer and partner support appears to have a greater benefit in preventing recurrence than other forms of support, but less benefit compared to drug therapy.

Comparisons of Psychological and Psychosocial Treatments

Studies that have compared psychological and psychosocial interventions have found that they all have similar effectiveness, though CBT may elicit better long-term benefits. However, the small sample sizes used in these studies may render their results unreliable. Various models of care, such as individualized treatment, combined psychosocial and pharmacological treatments, or a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, have been studied. There is no evidence to suggest that individualized care is harmful or safe, but it may not be as effective as other types of care. Combined treatment appears to be safe, but it is unclear if it is more effective than either treatment alone. A combination of psychosocial and drug interventions may reduce costs.

Other Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Postpartum Depression

Pharmacological treatment may be preferred if a mother cannot attend regular psychotherapy sessions or prefers this form of intervention. However, pregnant women are often concerned about the effects of drugs on their unborn child, which can make decisions regarding pharmacological treatment more difficult. Luckily, they are not the only treatment option. Nonpharmacologic treatment includes:

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), formerly called electroshock therapy, is a procedure performed under anesthesia that uses brief electrical pulses to produce seizures in the brain of patients who suffer from severe forms of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. The seizures alter brain chemistry and relieve symptoms of mood disorders. Side effects of ECT include headaches and changes in mood. Some consider ECT to be a last-resort treatment when other treatments have failed. ECT is also used to treat other psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, catatonia, and mania associated with bipolar disorder, severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, and severe chronic post-traumatic stress disorder cases. It is also sometimes used to treat agitation and aggression in people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Bright Light Therapy

Bright light therapy (heliotropic) involves exposing patients to light at sunrise or sunset. Light therapy has been used for many years for treating depression. The theory behind it is that exposure to bright light helps people’s brains reset themselves and produce higher levels of serotonin, which in turn will help alleviate depression. One meta-analysis found that bright light therapy had moderate evidence of effectiveness in treating depression and “moderate” effectiveness in improving sleep but no evidence of the effect on other outcomes commonly associated with depression, such as anxiety, appetite, cognition, or quality of life.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are known as essential fatty acids and are generally needed to maintain brain function. Many studies have shown that low levels of omega-3 fatty acids can lead to depression, especially if they occur before or during pregnancy. Researchers have found evidence to suggest that omega-3 supplements may be effective for treating American patients with major depression. This review found no effect of using omega 3 fat supplements on symptoms related to aggression or psychosis compared with taking a placebo. Moreover, when people were given a combination of both omega 3 and omega 6 fats, it made them feel less well than those who had only the omega 6 fats.

Acupuncture and Massage

Acupuncture is a Chinese medical treatment that has been used for centuries. It is based on the theory that energy or a vital life force called qi moves through pathways in the body. These pathways are called meridians. Some studies suggest that acupuncture can improve depression symptoms in the short term and maybe as effective as other treatments for depression in the long term. However, these findings have not been confirmed by researchers in larger studies. Massage therapy is a non-invasive way to decrease stress and anxiety and increase feelings of well-being. A 2010 review found no significant difference between massage therapy and relaxation therapy concerning reducing symptoms of depression, although both massage and relaxation therapies decrease anxiety symptoms.

Meditation

Meditation is widely recognized as an effective treatment for depression. The first peer-reviewed studies on

Exercise

Several studies have suggested that exercise has a beneficial role in treating depression. Exercise can also help normalize weight, often a significant problem for depressed people. However, exercise may have the opposite effect and trigger depression in some cases. This may be related to levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. Physical exercise can be postpartum depression natural treatment and a postpartum depression self care routine.

Patient Preference for Psychological Vs. Pharmacological Treatment

Postpartum depression is the most common complication after childbirth. The condition is associated with considerable maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide and has high costs from a societal perspective. Treatment options include psychological as well as pharmacological interventions. Although psychological interventions are more commonly used to treat postpartum depression, the effectiveness of these approaches is not well-supported. Most women in clinical practice present with a mixed diagnosis (depression and anxiety) comprising about 55% of the disorder for which psychotherapy provides little benefit. Lack of evidence does not mean that psychotherapies do not work. On the contrary, they have increasingly been shown to be helpful. We need a new strategy for treating postpartum depression that can be based on a more objective and rigorous approach. For example, systematic reviews and meta-analyses (MA’s) can provide valid treatment information by minimizing biases that introduce major flaws into traditional clinical trials.

Effectiveness of Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Postpartum Depression

There is no difference in the effectiveness of psychological and pharmaceutical treatments for postpartum depression when measured by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD). Researchers have provided evidence from randomized trials that suggest a better clinical outcome with pharmacological interventions versus psychological treatments. However, HRSD scores do not correlate well with functional outcomes such as work status and marital stability, suggesting that the decision to use pharmacotherapy should also be based on patient preference and informed by postpartum depression counseling. Psychological therapies have been shown to be as effective as pharmacological treatments for postpartum depression during a depressive episode. HRSD scores do not increase after treatment with certain psychotherapies until six months after childbirth. A Cochrane review has shown that interventions starting in the antenatal period were more effective in reducing maternal and infant morbidity, whereas early interventions during lactation had no benefit.

How Do I Know If I Have Postpartum Depression?

It’s hard to know if you have postpartum depression. As you may be feeling many emotions, including anxiety or fear, and believe that these are caused by postpartum depression. Or, you may not be experiencing any symptoms at all. If you think you may have postpartum depression:

- Check in with the other people in your life and see how they’re doing.

- Talk to your doctor or another health care provider about what’s happening to you. You don’t need a diagnosis of PPD for them to help.

- Have someone close to you take notes about what is happening every day (this can eventually include parenting skills). You might not notice subtle changes in your behavior. All of this will be important information for your doctor to know. If you think you might have postpartum anxiety or postpartum psychosis:

- Call 911, or call the police if you are afraid that someone will get hurt. Or, contact the police if you are talking to someone, and they tell you that they want to hurt themselves—you don’t want them to act on suicidal thoughts just because they have a bad thought during a bad moment.

- Call your doctor or another health care provider right away. Do not wait until business hours—call whenever it is safe and easy for you to do so.

What Will Happen During My Doctor’s Visit?

When you go to your doctor’s office, you may not know what to expect. Even if you’ve had newborn visits before, this visit will probably be different. Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and concerns—and about how you’re doing in general. They may ask the person who made the appointment with you how they think you are doing as a parent and how they think the baby is doing.

Preparing for Your Appointment

There are a few things you can do to make sure you get the most out of your appointment:

- Write down what symptoms you’re experiencing. You may think that family members will remember, but it’s hard to remember all the details accurately. And some symptoms, like forgetfulness and trouble getting organized, are subtle and can be missed.

- Bring a notebook or a recording device to your visit. Journaling is an effective way to help you process what’s happening to you. You can journal about whatever you want, but it’s a good idea to include the following:

- What your symptoms are

- How you’re feeling emotionally

- How long you’ve been experiencing these feelings and how they started (for example, “since right after the baby was born” or “since I had a rough day taking care of my two-year-old at this time last week”)

- What has helped (or not helped) so far

- During your doctor visit, it can be helpful to have someone record any numbers or information that come up—things like what medications you take or what number is on your blood pressure cuff. You might bring a tape recorder or recording device with you if you think it will help.

When Should I Call My Doctor?

If you have thoughts of hurting yourself or someone else, call 911. You can get help for these thoughts by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. They’ll help determine if you need an emergency doctor or an emergency room visit. If you call the lifeline, they will ask for your name and location—not your phone number—so the person who answers can refer the call to a mental health professional certified in suicide assessment and intervention (SAI). And you should never be afraid to call 911 because of your immigration status. If you’re in the U.S. without legal status, it’s still a good idea to call 911 if someone is at risk of hurting themselves or others. If you have symptoms that are not as severe, and you want more time to speak to your doctor, it’s also a good idea to call them. Or, if the symptoms change or get worse at any time during your appointment (or after an appointment), it’s essential to let them know that, too.

Do I Need Medication?

It depends on how severe your symptoms are and how long they last. If symptoms last for less than two weeks, most doctors will schedule a follow-up appointment. If your symptoms last more than two weeks, your doctor may recommend medication (depending on how severe they are), or they may suggest postpartum depression counseling or both. If you decide to take medication to treat PPD, be sure to take it as prescribed and in the correct dose. Do not stop taking the medication without speaking to your doctor first. To get the most out of PPD medications, take them regularly and at the correct times of the day.

Do I Need to Take a Leave?

For many new mothers, work is stressful and exhausting, even without adjusting to caring for a newborn. PPD can make the adjustment to being a mother even more difficult. You may experience a great deal of guilt and worry about how you are doing or about how much your baby is suffering, which can affect your ability to work. For some women, this results in taking a leave of absence because they feel that their job is too stressful to continue. If you take a leave of absence, you must know that it may not be enough to get your life back on track. If you decide to take leave:

- Talk to your employer and colleagues. You can ask for help in managing symptoms of PPD, especially if you feel that the stress at work is making those symptoms worse. If you have an employee assistance program (EAP) at work, check it out—it’s an excellent resource for navigating PPD.

- Talk to your doctor about what you’re going through at home and at work, as well as whether a leave of absence will make it easier for you to get treatment and heal from PPD in your daily life.

- Use your time off to focus on taking care of yourself, speaking to other people about what you’re going through, and better understanding how to integrate into your family’s life.

Should I Be Worried About Postpartum Psychosis?

If you are concerned about PPD, it makes sense to be worried about the possibility of postpartum psychosis because it is rare and does not happen to most women with PPD. Postpartum psychosis is a mental health disorder that can affect new mothers within the first two weeks after giving birth (but sometimes after an extended period). Hallucinations and delusions characterize it—and it’s serious, as it can lead to self-injury and suicide.

There are some specific warning signs that a person may be experiencing psychosis, including:

- Hearing or seeing things that aren’t there.

- Believing things that aren’t true.

- Having problems with reality testing (the ability to tell what is real and what isn’t).

- Hallucinations are usually accompanied by disorganized thinking (distorted thought process) and impaired social functioning.

- Postpartum psychosis can last a few days or weeks, and it can affect any woman who has just given birth. But the disorder is so rare that it’s not clear how many new mothers go on to develop this condition.

What Should I Do If I’m Concerned About PPD?

If you think you may be experiencing PPD, talk with your doctor right away. They’ll want to assess your symptoms and recommend postpartum treatment if needed—right then and there. And once you get help for your symptoms, make sure that you follow up with your doctor to make sure that the treatment is working and that you are making healthy changes in your life. Don’t self-diagnose; see a health care provider for an accurate assessment before taking any medication.

Can Postpartum Depression Affect Men?

Can men have postpartum depression? Yes, PPD can affect men, too. About one-fifth of fathers will experience some symptoms of PPD, which can include irritability, sadness, and anxiety. Can men have postpartum depression? It can be hard to believe because many people are still not sure if men can experience PPD or if they think it is just a “woman’s problem.” You see this, especially in the workplace—a woman with PPD may get sympathy and support from co-workers, but a man with postpartum depression may be considered weak or unsupportive.

However, men can experience PPD, whether they are new fathers or not. If you are feeling sad, anxious, or irritable after the birth of your baby or if you are having a hard time bonding with them, speak to your doctor or mental health professional. They can help you understand what is happening and get help for any problems that you may be experiencing. The first step is to decide if you need help. You should know what to do if you are concerned about PPD, including how to speak with your doctor about it and where to go for help.

What If I Already Have Postpartum Depression?

If you think that you have PPD and can’t seem to find the energy or make the time to get help, remember that you have a family who needs you, and there is nothing wrong with asking for support from others. In most cases, someone else may need to make the call for help because they’ll be able to explain your symptoms more clearly than you will. (This is especially true for men. If you are a new father, you may not feel comfortable telling others what is going on—if it makes you feel uncomfortable, have someone close to you call for help instead.) Or, if talking to someone on the phone isn’t right for you right now, you’re able to send a text message, write a letter or an email, or make a list of things that need to be done. Giving yourself some options can help reduce feelings of distress and anxiety. Grab a calendar, planner, or notebook and make notes about what needs to be done over the next few days. You may want to write down how you’re feeling, too. It can be helpful to keep a record of what you’ve been doing each day—even if it feels like nothing at all. If you are having trouble with this, try asking someone close to you for help, or suggest that they ask for professional advice for you. You may want to use a calendar or planner as a guide, or even make an appointment with your doctor or health care provider so that they can help you find the right mental health professional in your area. If talking on the phone is just too hard right now, have someone call and make the appointment for you. If you cannot call them back yourself, find someone else who can, or write down the instructions for calling on your calendar. You may also want to speak with friends or family members about the possibility of PPD. If you’re uncertain if you have PPD when you feel like this, share what is happening to someone in your life who has been through it before or loves to listen in support. Getting help is often a difficult first step—but it could benefit everyone involved.

Is It a Bad Idea to Talk to My Family About PPD?

It isn’t a bad idea at all. You may feel embarrassed, ashamed, or alone—but you are not. If your family knows what you are going through and how to help you, the burden on your shoulders can be lifted. They love you, want to help you, and know how important it is for your whole family that things start feeling better again soon. But if you feel that they cannot understand what you are going through, make sure to get a professional opinion before you decide that they don’t care. If your family believes that PPD is false or valid, they may not have enough empathy to realize how much help you need. Practicing Postpartum Depression Awareness Month every month of the year can help prevent PPD and other negative symptoms by getting the support and professional care you need before the baby is born. As with any type of mental illness, it is crucial to get help as soon as possible to manage your condition effectively. It can make a huge difference in your recovery process.

Recognizing Your Partner’s Postpartum Depression

The best ways to help a loved one suffering from postpartum depression are to show them love and support and speak to someone who can give them the help they need. As they work through their feelings and get professional care, you may be able to keep things steady at home by paying attention to their mood, sleep patterns, eating habits, energy level, and daily activities. If you find that there are specific things that you can do to help bring back the positive force in their life—like making sure that your home is clean, or that family time stays at a high priority—then do it. Whether you’re dating or just a good friend, recognize that PPD can affect people in different ways. While some may feel sad, irritable, and cry easily, others may withdraw from their family and friends. Recognize how your loved one is acting and search for the signs that may mean they need help.

How Can I Get Help?

If you or someone else in your life needs care for depression or PPD, there are resources available to help:

- Talk to somebody about what you’re going through (whether it’s a friend or an expert in the field). Don’t try to deal with it alone.

- Reach out for support from friends, family, or community organizations.

- Talk to your health care provider and ask for a referral to a mental health professional.

How to Help Someone With Postpartum Depression?

The most important thing you can do is offer support and love without judgment. It can be challenging to discuss feelings of depression and the feelings of guilt and inadequacy that often come along with learning that someone you care about is suffering in this way. So just being there—looking them in the eye, smiling, and talking to them—can go a long way toward helping them feel better. It’s important to know that there are plenty of things you can do to help make the situation easier. A lot has been written about how helpful it is to speak with your loved one, but talking isn’t the only important thing you can do to help. Your energy, patience, and willingness to help around the house (while they may still be struggling with symptoms) are vital steps toward assisting them to feel like themselves again. Some examples of ways that you can offer support include staying away from anything harmful or blaming. It is imperative to avoid criticizing, minimizing, or judging the feelings or actions of your loved one. Instead, be supportive and approach the situation with a gentle ear and an open heart.

What If They Don’t Want My Help?

Not everyone suffering from PPD will want to seek help from others. This is especially true if they are experiencing severe symptoms like thoughts of self-harm, suicidal thoughts, or attempts at taking their life. But it doesn’t mean that you should ignore what is happening. If you feel that they may be a danger to themselves, do your best to convince them to seek help. And if it is an emergency, call 911 right away. Your loved one can always heal more easily if they are not afraid of dying. Most people with PPD are aware that their behaviors and reactions are extreme, but this doesn’t mean that it is easy for them to accept help from others or acknowledge the issues behind their condition. They may feel embarrassed or inadequate, and this can make it difficult for them to ask for what they need—or even recognize what they need in the first place.

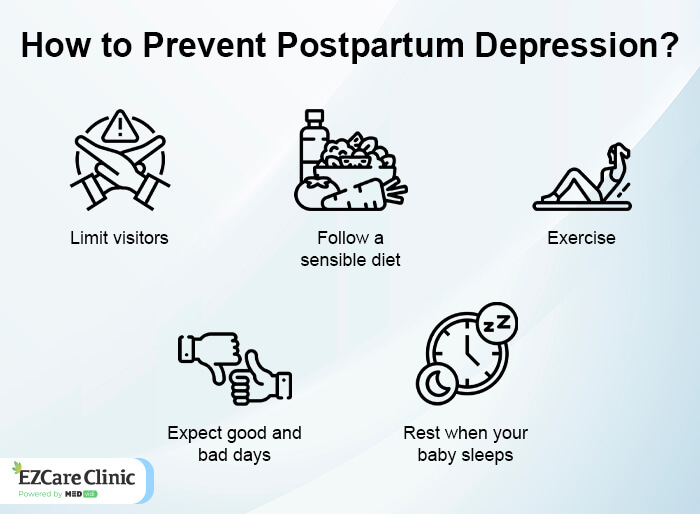

Postpartum Depression Prevention

Early treatment is the best way to prevent PPD. That means that you should see your doctor for an antenatal care check-up during your pregnancy and again within the first two weeks after you give birth. By talking about any additional stressors in your life, getting help for any health issues that may be affecting you, and sharing how much support (social, emotional, or financial) you have in your life—you can start preparing for a healthy postpartum period. In addition to receiving early care, there are things that you can do before and after birth to help prevent PPD (or minimize symptoms if it does happen). If you intend to become pregnant, take steps to increase your chances of a healthy pregnancy.

- Stop smoking. If you are already planning to quit, now is the time to start. And if you are a smoker, get help now.

- Get educated about the signs and symptoms of PPD (even if you don’t have them).

- Learn how to manage stress in healthy ways by eating nutritious foods and doing relaxing activities that can help prevent or manage stress (like yoga or meditation).

- Attend certified childbirth preparation courses that include information about the normal emotional, physical, and psychological changes of childbirth.

- Become familiar with the special needs of women who have given birth (like postpartum depression or loss of pregnancy).

- Make time for the support you need—whether it’s a weekly or daily routine of spending time alone having one-on-one conversations.

After your baby is born, continue to take care of yourself. Take time to rest and relax. Move your body (like taking a walk outside) or engage in pleasurable activities (like gardening) that can help keep feelings at bay. Talk to people who you know and trust. Don’t be afraid to ask for help if needed.

And, just as important, don’t spend too much time worrying, either. The most helpful thing that you can do is make sure that you have a healthy pregnancy and birth, followed by time alone to recover while your baby is forming close bonds with the world around them (so that you can get back to work again).

Contact us or click the banner below to schedule your appointment to overcome postpartum depression at EZCare Clinic.

Sources

- Postpartum Depression

Source link - Biological and Psychosocial Predictors of Postpartum Depression: Systematic Review and Call for Integration. (2017)

Source link - The relationship between postpartum depression and breastfeeding. (2012)

Source link - Depression Among Women

Source link - 3006 â Maternal borderline personality disorder and the peripartum: challenges for mother and infant. (2013)

Source link - What is Peripartum Depression (formerly Postpartum)?

Source link - Incidence of maternal and paternal depression in primary care: a cohort study using a primary care database. (2010)

Source link - Treatment of Substance Use Disorders Among Women of Reproductive Age by Depression and Anxiety Disorder Status, 2008-2014. (2019)

Source link - FDA In Brief: FDA takes action to ensure regulation of electroconvulsive therapy devices better protects patients, reflects current understanding of safety and effectiveness. (2018)

Source link - How meditation helps with depression. (2021)

Source link - Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. (2012)

Source link